Scale2Save Campaign

Micro savings, maximum impact.

Editor’s note: This article is part of NextBillion’s series “Enterprise in the Time of Coronavirus,” which explores how the business and development sectors are responding to the pandemic. For news updates and analysis, virtual events, and links to useful resources related to the COVID-19 crisis, check out our coronavirus resource page.Last year I was part of a team that conducted a Financial Diaries study of young people in Morocco, Nigeria and Senegal as part of a comprehensive research project on “Young People in Africa” that was conducted on behalf of the Scale2Save Programme — a partnership between the World Savings and Retail Banking Institute and the Mastercard Foundation. The team has produced a comprehensive report on our findings, but we also wanted to share some of what we learned in a more accessible format, and to explore the implications in light of COVID-19. This is the first of three NextBillion articles coming out of that study – you can read the second article here, and the third one here.Young people in Morocco, Nigeria and Senegal tend to live in their parents’ homes until around 25 years of age. They maintain a strong connection to their parents when living at home, and that bond remains when they move away. In this context, parents often provide financial and other support to their children. But is this always the case? And if not, what are the implications for financial service providers and financial inclusion promoters?

In this study we asked young people to tell us about any support they had given or received from various members of their family, as well as friends and neighbors. The answers suggest a complex, dynamic interplay between parents and their children that extends beyond a one-way dependency of young people on their parents – especially among the Morocco sample of young people.

In the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdowns it entails, opportunities for young people to earn money have been hit hard – and their parents are facing similar challenges. We do not know the ultimate impact of the pandemic on families, but the financial diaries data we’ve gathered suggest that it will affect both the economic activities of individual family members and the economic relationships among family members.

CONTEXT MATTERS

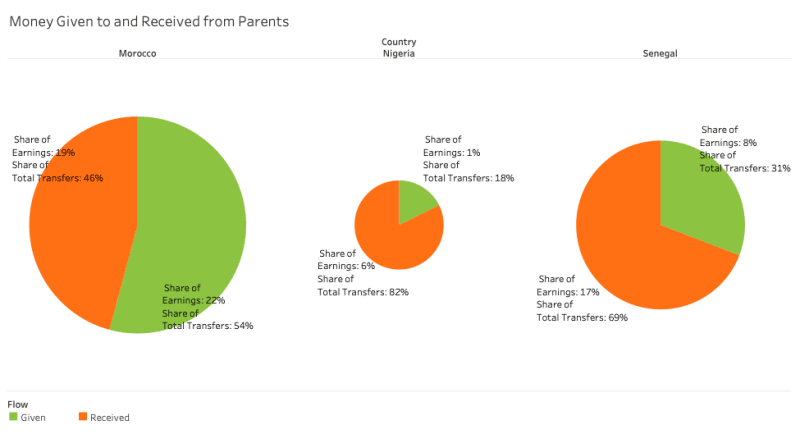

There was considerable variation in the amount of money young people gave to or received from their parents during the study. This variation may not be generalizable to the young people in the country as a whole because of the small sample size, but it is indicative of how different parent-child financial relationships can be. For instance in Morocco, young people gave more to their parents than they received, while in Senegal young people gave less than half what they received from their parents. In Nigeria, it was less than a quarter. Furthermore, in Morocco transfers of money were far greater as a share of the total earnings of participants in the diaries studies: Transfers there amounted to 41% of the participants’ earnings, while in Senegal they were 25%, and in Nigeria only 7% (Figure 1).

In Figure 1 the size of each pie shows the total amount of transfers as a share of earnings—the bigger the pie, the bigger the amount of transfers relative to the respondents’ earnings – while the slices of the pie show the share of transfers received by the diaries participants and the share of transfers they gave.

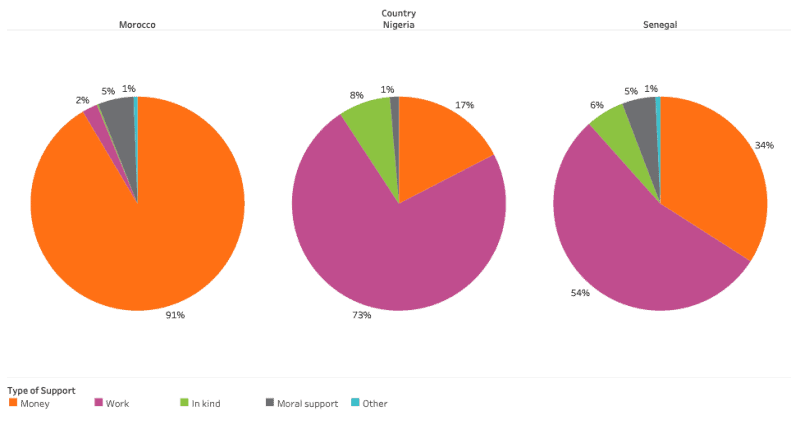

These financial support patterns should be seen in light of the overall support that young people receive and give. For example, the Moroccan young people overwhelmingly reported giving their parents financial support as opposed to in-kind or work support. In contrast, in Nigeria, young people only gave financial support in less than 20% of all instances when they gave their parents support. In most instances, they supported their parents with work. In Senegal, 34% of instances were in the form of money and 54% in the form of work (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Type of Support Given by Young People to their Parents

MOTHERS MATTER

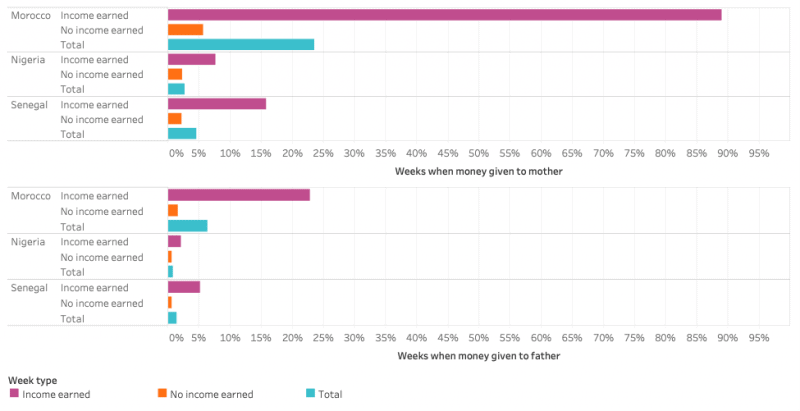

Generally, young people in each country worked or participated in a business activity about half the time or less: 46% of the time in Morocco, 52% of the time in Nigeria, and 34% of the time in Senegal. But when they did work, they gave money to their parents, especially their mothers and especially in Morocco — in almost every week that they worked, young Moroccans gave money to their mothers. In contrast, they only gave money to their fathers in less than a quarter of the weeks when they worked. Young Senegalese and Nigerians were generally less likely than young Moroccans to give money to their parents in weeks when they earned, but, as in Morocco, mothers were still their priority (Figure 3) when they did give money to their parents.

Figure 3: Share of Weeks when Money Given to Parents, by Week Type

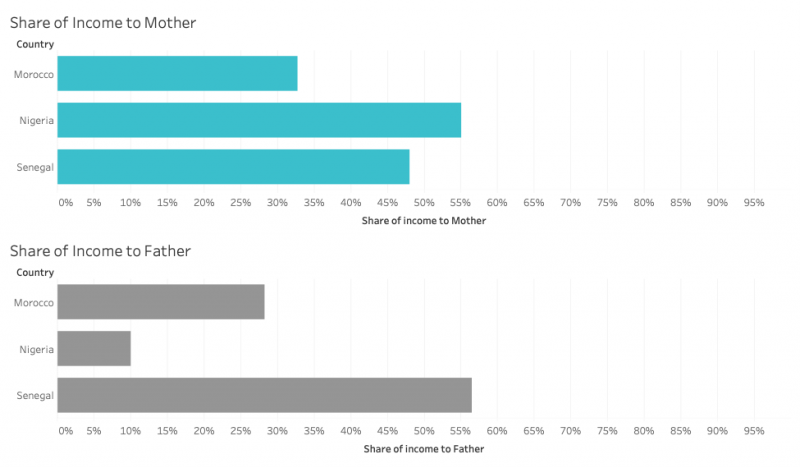

Finally, we are able to use the diaries data to see how much of their income young people gave to their parents in weeks when they did give them money. We calculated the amount they gave as a share of their reported earnings during the week when they gave money. As shown in Figure 4, the data suggest that in Morocco, when young people gave money to their mothers, it constituted about one-third of their income for that week. The same was true when they gave money to their fathers — but note that they gave to their fathers far less often, hence the total they gave to them was less. In Senegal, when young people gave money to either their mother or father, they gave around half of their earnings. In Nigeria, they gave about half of their earnings to their mothers, when they did give money, but little of their weekly earnings to their fathers. But, again, it is important to remember that these calculations are just for weeks when a young person gave money.

Figure 4: Share of Weekly Income Given to Parents During Weeks when Young People were Working

GIVING: A TWO-WAY STREET BETWEEN PARENT AND CHILD

The data on the behaviors of the groups of young people in the countries covered by the financial diaries study suggest a wide variety of relationships between young people and their parents. This may have something to do with the differences in the cultures of the three countries, but it may also have something to do with differences in sampling—i.e.: who we were able to talk to and the type of communities they lived in—across the countries.

In a nutshell, the data show how young people support their parents, both financially and through work and in-kind gifts, as well as how they receive support from their parents. In the case of young people in Morocco, the amount given exceeded the amount received, and their giving was common and frequent and constituted a third of their earnings (when they did earn). In Nigeria and Senegal, young people were more likely to support their parents by working for them. In the time of COVID-19, economic resilience is more important than ever. Depending on which generation in a family is most adversely affected by the pandemic, we would expect the other generation to increase their support. In many families we’d expect young people to play a critical role in strengthening family resilience through the support they give to their parents. On the other hand, in cases where young people have been disproportionately hit, we’d expect parents to step up their support for their children, whether they’re still living at home or not.

What does this suggest for financial service providers and others interested in promoting financial inclusion? One key takeaway is that taking a close look at the relationship between young people and their parents – and especially their relationship with their mother – can help providers work out the best ways to connect young people to financial institutions. This raises the question: Could mothers become allies in promoting the accumulation of savings in a young person’s bank account, in the purchase of health insurance, or in the use of other types of financial services? In the next two articles in this series, we’ll discuss these questions – and explore ways that providers can strengthen the resilience of families in the context of COVID-19 by making it easier for money to flow among family members in mutual support of each other.

Scale2Save

13/10/2023

Savings and Retail Banking in Africa 2022 WSBI survey of Financial Inclusion for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs)

The Savings and Retail Banking in Africa report aims to help improve access to financial services for financially

25/09/2023

WSBI as a catalyst for unlocking the potential of female entrepreneurs

13 October 2023, 9.30am-12pm Hôtel Du Golf Rotana Palmeraie, Marrakech I Morocco

18/09/2023

WSBI’s MD Peter Simon opens the G20 side event panel “Gender equity and SME financing in a digital landscape” at the SME Finance Forum in Mumbai

The World Savings Bank Institute (WSBI-ESBG), with the substantial support of its Indian member, the State Bank of India

01/03/2023

The State of Savings and Retail Banking in Africa

The WSBI has conducted two research reports tracking the progress of retail and savings banks in their financial inclusion efforts across Africa (2018, 2019).

22/02/2023

Driving Formal Savings: What Works for Low-Income Women?

While financial inclusion is expanding globally, the gender gap in access to financial services and products persists

19/12/2022

What a journey it has been!

Between 2016 and 2022 Scale2Save financially included more than 1.3 million women, young people and farmers in Kenya, Uganda, Nigeria, Morocco, Senegal and

14/12/2022

The financial diaries revealed useful insights into young people’s savings, spending and income behavior

It examines their experience in respect to financial inclusion, support structures and opportunities for young entrepreneurs

09/12/2022

The Power of Community-Based Organizations to Mobilize Farmers’ Savings

In Ivory Coast, the world’s largest cocoa producer, cocoa is harvested twice a year, in May-June and in October-December. Between seasons, most smallholder farmers do not generate revenue

15/11/2022

How Can Small Scale Savings Be Offered Sustainably?

Learnings from the Scale2Save Program on successful business and institutional models

15/11/2022

Application of CGAP Customer Outcomes Framework in Uganda

This case study by WSBI's Scale2Save programme applied the CGAP customer outcome indicator framework to test the impact of a new basic savings product positioned in the financial inclusion market and…